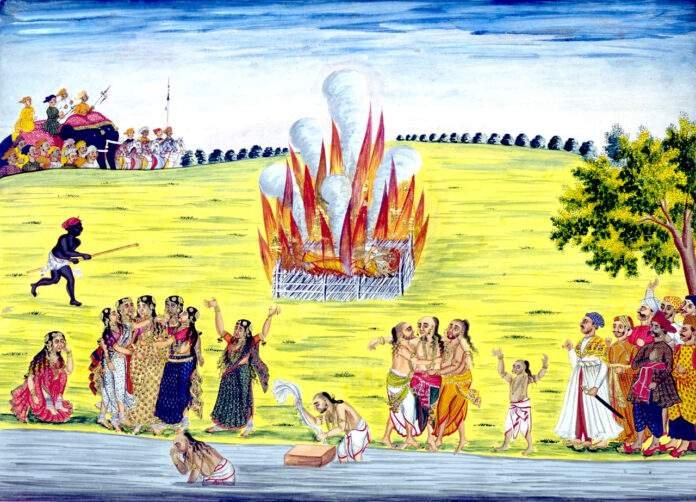

Sati Pratha, the practice where a widow immolates herself on her husband’s funeral pyre, is one of the most controversial and debated customs in Indian history.

Sati Pratha

Rooted in ancient traditions, this practice has both horrified and fascinated scholars and historians alike. Understanding Sati Pratha requires delving into its origins, cultural significance, evolution, and eventual abolition.

Historical Origins

The term “Sati” is derived from the Sanskrit word “Sat,” meaning “truth” or “goodness.” The practice is believed to have originated from the mythological story of Sati, the wife of Lord Shiva, who self-immolated in protest against her father’s insult to her husband. However, the historical origins of Sati as a social practice are less divine and more complex.

Sati is first mentioned in ancient Hindu scriptures such as the Mahabharata and some Vedic texts, although it was not prescribed as a religious duty. Over time, it became more prevalent, particularly among the warrior and royal classes, where it was seen as a demonstration of ultimate loyalty and devotion by the widow.

Cultural Significance and Justifications

Sati was often justified on religious and socio-cultural grounds. It was believed that a woman who committed Sati would attain Moksha, or liberation from the cycle of rebirth, and ensure a place in heaven for her husband. The widow was idealized as a paragon of virtue, and her sacrifice was seen as a purifying act.

Several socio-economic factors also played a role. In patriarchal societies where women were often seen as dependent on their husbands, the death of a husband left a widow vulnerable. By committing Sati, she was spared the potential indignities of widowhood, which included social ostracism, economic deprivation, and a life of asceticism.

Regional Variations and Practices

Sati was not uniformly practiced across India. It was more prevalent in certain regions and among particular communities. In Rajasthan, for example, the Rajput clans, known for their warrior ethos, observed Sati more rigorously. Bengal also saw a significant number of Sati cases, which drew considerable attention during the British colonial period.

The method of performing Sati varied. While self-immolation on the funeral pyre was the most common method, there were instances where widows were buried alive or forced to die in other ways. The practice was highly ritualized, involving elaborate ceremonies and community participation.

Criticism and Reform Efforts

Despite its glorification, Sati was not universally accepted or practiced. Many ancient texts and scriptures, including the Manusmriti and the Arthashastra, do not endorse Sati and instead prescribe a life of celibacy and austerity for widows. Over the centuries, various voices within Indian society have spoken against the practice.

One of the most notable critics was Raja Ram Mohan Roy, a social reformer in the early 19th century. Roy, horrified by the death of his sister-in-law who was forced to commit Sati, launched a campaign against the practice. His efforts included lobbying the British authorities, writing articles, and mobilizing public opinion. Roy argued that Sati was not an essential part of Hinduism and was instead a barbaric custom that needed to be abolished.

Colonial Intervention and Abolition

The British colonial administration in India initially hesitated to interfere with local customs and religious practices. However, mounting pressure from reformers like Raja Ram Mohan Roy and growing outrage in Britain over reports of Sati led to a shift in policy.

In 1829, Lord William Bentinck, the then Governor-General of India, passed the Bengal Sati Regulation, officially banning the practice of Sati in Bengal. This regulation was extended to other regions under British control in the subsequent years. The abolition of Sati was one of the earliest examples of social reform in colonial India, driven by a combination of humanitarian concern and political pragmatism.

The banning of Sati was met with resistance from orthodox sections of society, who viewed it as an attack on their religious freedom. However, sustained efforts by reformers and the colonial government gradually led to the decline of the practice.

Legacy and Contemporary Reflections

The abolition of Sati was a significant milestone in the history of social reform in India. It paved the way for other reforms aimed at improving the status of women, such as the prohibition of child marriage and the promotion of widow remarriage. However, the practice left a deep imprint on the cultural memory and continues to be a subject of intense debate and reflection.

In modern India, Sati is a criminal offense under the Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act of 1987. This law was enacted following the infamous case of Roop Kanwar, an 18-year-old widow who was forced to commit Sati in Rajasthan in 1987. The incident sparked nationwide outrage and renewed efforts to enforce laws against the practice and protect the rights of widows.

Sati also remains a powerful symbol in Indian literature, cinema, and art. It is often invoked in discussions about gender, patriarchy, and the intersection of tradition and modernity. The legacy of Sati challenges contemporary Indian society to reflect on its history and continue striving for gender equality and social justice.

Conclusion

Sati Pratha, with its complex history and cultural significance, serves as a stark reminder of the deep-rooted gender inequalities that have plagued societies across the world. The journey from its glorification to its abolition underscores the transformative power of social reform and collective action.

While Sati is now a thing of the past, the struggle for women’s rights and social justice continues. The story of Sati Pratha is not just a historical account but a call to recognize and address the ongoing challenges faced by women in India and around the world. By understanding and learning from history, we can work towards a future where equality, dignity, and respect are the norms for all individuals, regardless of gender.

ALSO READ: FAMOUS FEMINIST APARNA DUTTA MAHANTA FROM ASSAM PASSES AWAY AT 75